It’s so often tossed about in the tech press that it’s almost blasé: Self-driving trucks may eliminate the human truck driver. “Yes, yes, jobs lost, dogs and cats sleeping together,” they seem to say, “but did you see that Apple might not include a headphone jack on the iPhone 7? It’s User-Hostile and Stupid!”

I guess the (possible) end of the headphone jack is more exciting than the definite end of a 20th-century blue collar career. Even the folks who are building self-driving trucks think it’s boring — To quote the founder of one autonomous trucking startup,

“Trucks are unsexy, and that’s why we’re doing it.”

Which is weird because trucking employs millions of Americans. If people do write about it, it’s just to support their own purposes — They’re running a freight company, interviewing an autonomous trucking CEO, or advocating for Universal Basic Income. Even I’m just doing it so I can drop a bunch of references to the second-highest grossing film of 1977.

Apple Watch Part III ETA: Someday?

But it deserves the attention, so grab yourself a Diablo Sandwich and a Dr. Pepper ’cause we’ve got a long way to go and a short time to get there.

Loaded up and Truckin’

Long-haul trucking is hard work. Drivers put in 14 hour days, up to 70 hours per week. They can be expected to drive 125,000 miles a year. And it’s dangerous — Piloting an 80,000 lbs vehicle requires constant vigilance. Weather, mechanical failure, and fatigue are all ever-present risks. Large trucks are just 4% registered vehicles in the US, but they’re involved in 11% of fatal crashes.

In addition to all of the above risks, other drivers aren’t exactly improving the situation. Amateurs drive drunk, read text messages, or even take pictures for their blog post (ahem). If you work in an office, imagine working with the possibility that a stranger could crash a car head-on through your window at any time. Why put up with that?

Because it pays well: Drivers can make $35,000+ in their first year and with the right experience and a good employer, they can rise past $70,000/year. If they’re entrepreneurial, they can make even more as an Owner-Operator. All of this without college: Earning a Commercial Driver’s License takes just 3 weeks and costs $5,000 (less if a future employer pays your way). A high school diploma is recommended but not required.

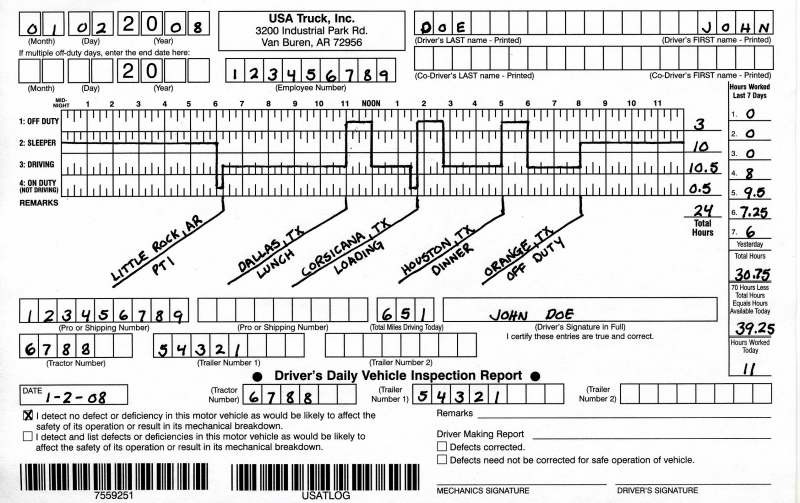

Hmm. I don’t think Snowman filled one of these out.

Drivers are often paid by the mile, but that’s not a license to print money: Since 1938, hours of service in the U.S. have been capped one way or another by the Feds. Currently, truckers can drive up to 11 hours per 14-hour work day. Each work day and every work week must be followed by mandatory rest periods.

Thanks to these rules, only 1.4% of those fatal accidents are due to driver fatigue. But it also means that keeping trucks moving 24/7 is complex and expensive. For example, if we make a few assumptions:

Paying $19.36/hour (the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ median wage)

An average speed of 55MPH during work days

Maintenance every 25k miles (Freightliner-recommended)

It will cost over $160,000/year to run a vehicle around the clock, which is more than the truck itself (a decent sleeper-cab costs only $140,000). It’s no surprise that there are almost as many trucks on the road today as truckers.

We don’t know what autonomous technology will cost on top of current truck prices, but a Boston Consulting Group report from 2015 gives us an idea. They estimated that last year’s research equipment added $43,000 per vehicle — about the same as one human driver, except robots don’t need to need to eat or sleep.

BCG also predicted self-driving features could drop as low as $6500 in consumer vehicles over the next 10 years. Since a self-driving truck wouldn’t need a sleeper cab (which adds at least $15k to a truck’s price), it could eventually be cheaper than the trucks of today.

Unemployment Bound and Down

We’re already seeing driver-assist features in premium truck cabs and consumer vehicles. The general public is comfortable with their cars parallel parking, cruising, and lane-keeping. Crazy early adopters are overreaching:

Oh, Vertical Videos. Why can’t we quit you?

Anyway, how long do we have?

In that report last year, BCG projected that consumer highway driving would be ready by 2017, with full autonomy arriving in 2025.

At the Re/Code conference a few weeks ago Elon Musk said that he believed driving was mostly a ‘solved’ problem, but regulators would hold up the technology such that we have 3–8 years until full autonomy.

At SXSW this year, Chris Urmson (head of Google’s self-driving car project) said, “How quickly can we get this into people’s hands? If you read the papers, you see maybe it’s three years, maybe it’s thirty years. And I am here to tell you that honestly, it’s a bit of both”

Based on those expert opinions, we have 3–11 years until the first vehicles are ready. Once that happens, the industry will still need to turn over existing facilities and vehicles through conversion or replacement. It might even be necessary to keep humans around for city driving long after highway driving has gone to the robots.

In a way, this reminds me of Containerization. Once upon a time, all cargo was ‘break bulk’ — Dock workers were necessary to carry each barrel, bundle, box, or bale on and off every boat. The work was physically hard, but it paid well and with growing global trade, it seemed quite steady.

Mclean’s first container ship, the SS Ideal X, set sail in 1956

Then, in 1955, Malcolm Mclean worked with Keith Tantlinger to develop the first (successful) shipping container. Instead of requiring workers to carry everything by hand, a solo crane operator could move a truckload in seconds. It would revolutionize the industry. Here’s how one longshoreman described it:

When we used to load sugar onto the ships in 125-pound sacks, each ship was a seven-day job. Now, with the bulk ships, they blow in a full load in eleven hours. There were 370 longshoremen in the port. Now there are thirty-five.

Even though Mclean opened his patents, the ISO didn’t publish the first international standards until 1968. By 1971, dock worker unions were regularly stipulating ‘work preservation’ clauses in contracts, but those were eventually gutted by the Federal Trade Commission and the old break bulk work was gone from the U.S. forever.

From its invention, containerization took over 20 years to reach an agreed-upon and well-installed standard. New trucks had to be developed. Dockyards had to be redesigned. Ships had to be re-fit or built new. The diffusion of technology was shaped by the acquisition of new equipment.

Trucking will similarly not change overnight, but much automation has already occurred — Trucks have transponders with GPS to report their location. PrePass (and similar systems) automate IFTA compliance at weigh stations. And highways are a small slice of what Elon Musk calls the “problem” of self-driving.

Since ~10% of the heavy truck fleet turns over annually, it might take a decade. But adoption tends to accelerate, like the transition from film to digital cameras, which started in 1999 and was over by 2005:

Analog cameras are basically gone, except from a few niches.

My prediction is that switching to autonomous trucks will take as little as 5 years once it begins. The recent accidents involving Teslas on ‘Autopilot’ might have pushed the start line out a bit. Which isn’t good news because of the peculiar demographics of truckers.

Watch Old Bandit Run

Researchers at the University of Leeds have a theory that the years in your life between 12 and 22 are the most influential. The “emergence of a stable and enduring self” makes those experiences particularly formative. Maybe not coincidentally, then, the average trucker today was 16 years old when Burt Reynolds and Jerry Reed made their beer run to Texarkana.

According to the ATRI, that generation has been the core of the transportation industry for more than twenty years:

This is from 2013, but continuing driver shortages and a steadily advancing ‘average age’ suggest the trend continues.

Half of current U.S. truckers are approaching Social Security/Medicare eligibility and younger people have (so far) been reluctant to take the job. That’s why the question of when matters a great deal. If the transition happens soon, retirement programs can soften the blow and robots will fill an growing labor shortage. If it’s a decade or more, the workforce will have shifted to be Millenial-heavy and we’ll have a bigger problem.

Evaluating how big our problem is brings me to one last analogy: The offshoring of American manufacturing.

This graph is from an upcoming paper in the Annual Review of Economics entitled ‘The China Shock: Learning from Labor Market Adjustment to Large Changes in Trade,” By David H. Autor (MIT), David Dorn (University of Zurich), and Gordon H. Hanson (UCSD).

I’ve reviewed both that and their previous piece (“The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States”) and while I’m not an economist, together they paint a grim picture of the collapse of American Manufacturing in the most affected areas:

Each direct job loss caused up to 1.7 other indirect job losses

Competition for the remaining jobs lowered per adult income by $156

Non-college-educated workers were affected disproportionately more

Government ‘Transfer’ payments (e.g., foodstamps, disability) rose markedly, with ~47% of the increase in income assistance programs.

Unlike factory employees, truckers enjoy the freedom to live anywhere they choose— And they often do. To bring this home, let’s ballpark the effect on a place like, say, Texarkana by using BLS and Census data for the region:

1,950 Heavy Truck Drivers

56,760 Total Workers

107,614 Adults (est.)

3.9% Unemployment

$38,020 Average Local Wage

If 50% of the heavy truck drivers are laid off and the resulting average decline in annual wages is $150/adult, my model shows a pretty dark economic outcome:

$116M drops out of the metropolitan area, representing (according to the BEA) a 2.3% drop in regional GDP. Depending on when the jobs are lost, local unemployment could spike over 8.5%. It would be pretty bad, and that’s if only half the truckers are laid off. Losing all of them would be crushing, with unemployment spiking up as high as 13%.

Zooming out, it would be unevenly bad for the nation, hurting smaller towns at the center of the country the most. Possibly because of the lower cost of living and lower tax rates, that’s where Truckers make up the highest percentage of the workforce. In San Francisco, CA they’re less than 0.3% of the workforce, but in Joplin, MO they’re over 5%.

Truckers (per thousand workers), shaded by Projected Unemployment

Admittedly, the analogy between the decline of U.S. manufacturing and the Truckpocalypse is imperfect. But twice as many trucking-related jobs are at risk as were lost in the last twenty years of offshoring. And the trucking jobs will dry up 2–4 times as fast. It’s going to be rough.

They’re Gonna Do What Can Be Done

It’ll start out west where roads are long and populations are thin. In a demonstration, someone will run an autonomous truck between two cities and across a state line, e.g., Denver to Kansas City. If urban autonomy isn’t viable yet, they’ll employ two drivers, one in each city, to serve as a ‘harbor pilot’ in charge of navigating to or from the city limits.

This will do more than previous demonstrations; it’ll show that an autonomous vehicle can comply with those IFTA payments by navigating through a weigh station at the border (you know [the Government] gotsta get paid). The results will be compelling: Even the ‘harbor pilot’ approach will take 80–90% fewer man-hours than a full-time driver.

From that route outward, it’ll expand across the country. The change will cut truckers in three ways: It’ll take away the most lucrative work (the long, uninterrupted miles), it will reduce the total number of driving jobs, and the freedom of the trucking lifestyle will disappear for those that stay employed.

More germane to this post: It will render my whole cinematic conceit moot. With a robotic truck and current speed limits, the film’s orignal challenge could be done legally in 20 hours, blowing away the Burdettes’ 28-hour deadline. There’s no need for a blocker car; no need for Bandit Darville. And without the Bandit to pick up Frog as she flees from her wedding, there’s no need for Buford T. Justice, AKA Smokey, to chase them across five states.

The result of the Truckpocalypse won’t be Smokey and The Robot, it’ll just be millions of driverless trucks cruising at a reasonable speed, uneventfully through the night.